Art Crime and Carabinieri

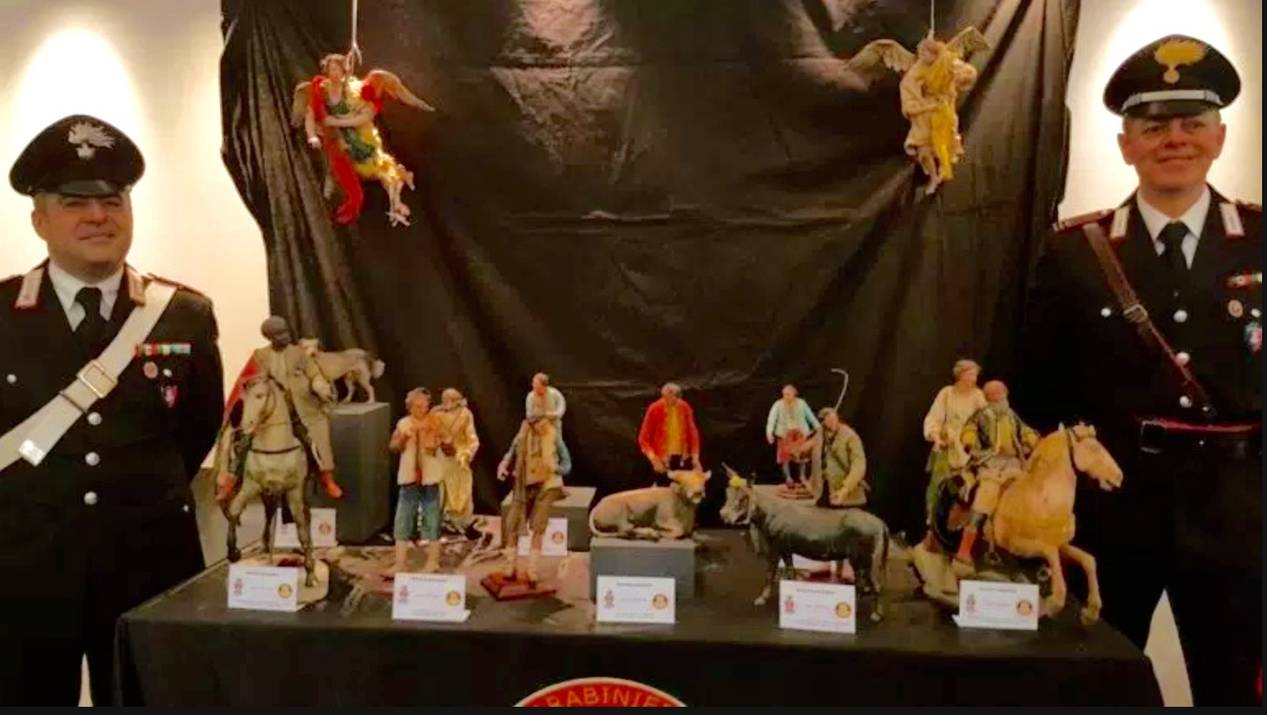

ROME -- In a post-Christmas season bonus, the Italian Carabinieri art squad held a press conference in Rome Jan. 12 with a showing of their latest art recovery: 250 figures from an 18th century Neapolitan presepe, or creche, with an estimated value of $2.4 million. The presepe figures were found in Christmas creches all over Italy, said General Fabrizio Parrulli, who heads the Carabinieri for Protection of the Cultural Heritage (TPC). To date the owners of 49 of the recovered figures have been identified, said Isernia prosecutor Paolo Albano, who oversaw the investigation.

"This case is unique in that our investigation was facilitated by an efficient data bank," said Col. Carmelo Marra of Naples. The thefts took place in 1999-2000 in the Church of Sant'Agnello on the Sorrentine coast and in two private homes in Naples. So far 20 individuals risk trial. The remaining 201 figures for the moment are being overseen by a foundation, which plans to put them on display in showcases in Naples before Easter, he added. "We are also in contact with New York Mayor de Blasio for a possible contribution for the exhibition," he said. Also under consideration: creation of a permanent exhibition on figures from the Neapolitan presepe.

The trend nevertheless is for a demonstrable reduction in art crimes, down from 906 in 2011 to 449 in 2016, according to ANSA. Still, with its historical abundance in works of art and archaeology, Italy remains the single largest market for stolen works of art, with perhaps 20,000 art thefts a year or 55 a day. Half take place in private homes, while one out of ten is from an art gallery, according to a study made last year by the Italian Chamber of Commerce together with Interpol, the Carabinieri art squad and the non-profit Association for Research into Crimes against Art (ARCA). The thieves' favorites begin with rare postage stamps. Second are sculptures followed by paintings and drawings, with at the bottom of the line sacred relics and jewelry.

The efficiency of the Carabinieri art squad is a crucial element behind the decrease in the number of art thefts in Italy and the number of recovered objects, including the shepherds from the Neapolitan creches. Under the late Carabinieri General Roberto Conforti, who retired in 2001 and died last July, Italy launched myriad international initiatives aimed at wiping out the illicit worldwide traffic in stolen works of art. For 42 years, from headquarters at Rome's Piazza Sant'Ignazio, General Conforti, who was born at Serre near Salerno, oversaw the recovery of thousands of art works stolen from private collections, galleries and museum. He was not only a pioneer in Italy, but he and his team of 300 taught police in other countries how to conduct their investigations and to work together. On Jan. 10 his work was honored by a conference called "A Life for Art," held in the Campidoglio in Rome.

If this is the good news, the bad is that a major holiday heist that made news worldwide is yet to be resolved. The theft Jan. 3 of exotic, diamond-studded jewelry came on the very last day of the three-month exhibition in the Palazzo Ducale of Venice called the "Treasure of the Mughals and the Maharajahs." Two (and perhaps three) thieves brazenly ripped open a glass display case and slipped as if invisibly into the huge holiday crowd. Within literally seconds they had tucked into their pockets two earrings and a diamond brooch from the Sheik Al Thani collection, on loan to Venice from the royal family of Qatar. Strolling away, two of the thieves were photographed, but not captured.

Some of the 270 pieces of jewelry on view, inspired by and made in the Indian subcontinent, date from five centuries ago. Fortunately, the stolen items are contemporary, and consequently of less historical (and monetary) value than other items on view. Initially reported as a $1 million heist, the value of the stolen objects is now put at perhaps $360,000. (Watch it live in this Corriere del Veneto video taken from a security cameras here >>).

The Fake Modigliani Issue

Art theft takes other forms than outright theft, however. Twenty-one paintings from an exhibition at Palazzo Ducale in Genoa of 70 works attributed to Amedeo Modigliani have been seized as fakes. When the exhibition opened last March the Tuscan expert Carlo Pepi immediately identified the works as counterfeit, and experts now agree. In his defense, exhibition curator Rudy Chiappini insists that the works on view were all previously shown in other prestigious venues. But technical experts point out that canvas and pigment are unlike those in authentic Modigliani works and that the frames of the paintings are all of wood from the US or East Europe, with no relation to works by Modigliani, who lived between Italy and France.

A problem with Modigliani is that no catalogue raisonné exists of his work. Christian Parisot, who had inherited the right to guarantee authenticity, was arrested in 2013 by Roman investigators for providing false authentications. The fallout from the Genoa fiasco has terrified Modigliani collectors worldwide, to the point that in the future, "There will be a counter-technical expertise report," as one commentator here predicted. At any rate the selling of phony Modigliani continues because, say experts, his paintings are popular, his life romantic, the style of his work lends itself to imitation, and, best of all, works attributed to Modigliani sell for vast amounts of money.

i-Italy

Facebook

Google+

This work may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without prior written permission.

Questo lavoro non può essere riprodotto, in tutto o in parte, senza permesso scritto.