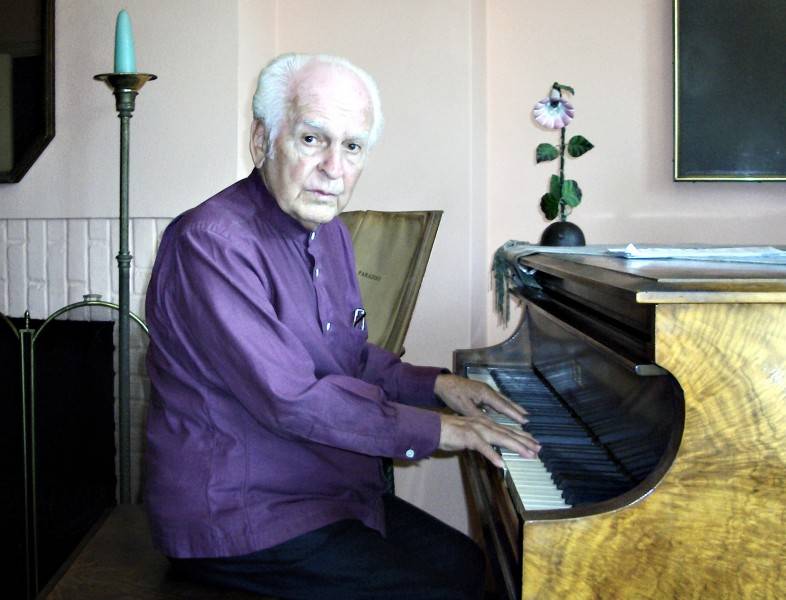

Anton Coppola: Maestro …by All Means!

A musician, composer, conductor and teacher, he is among the most renowned in the world and the bright symbol of Italianità in the classical music field. Needless to say the interview is in Dante’s language: “Parla Italiano? Mi difendo” starts funnily Maestro Coppola.

His parents arrived in the United States in 1904; his father from Bernalda (Matera) and his mother from Tricarico (Matera), both of lucan origin (Lucania is the other name for the region Basilicata). He was born and raised in East Harlem, at a time when it was almost exclusively an Italian enclave.

“My uncle Giuseppe, owner of a popular barber shop in the area, had an unstrained passion for Opera and used to bring me to see performances at the MET.

I was only a child, but already had a perception of how much Opera was one of the reasons to be proud of being Italians, especially for those who had just emigrated from their homeland and were a having hard time in their daily struggle to survive.”

Nevertheless it’s not surprising that, especially at the beginning of the last century, Italians performed almost all the Operas and the MET general manager, Gatti Casazza, was also Italian. Italians interpreters like Enrico Caruso, the legendary Neapolitan tenor, and the very remarkable bass Ezio Pinza are good examples to demonstrate how some were able to climb the operatic boundaries and assert themselves as relevant personalities among the world’s stars.

A childhood spent behind the back stage: “ my uncle would often take me behind the stage, to the dressing rooms, between busy crew members and singers in costume ready to step onto the stage and sing their challenging arias, in a mix of nervousness, anxiety, and superstition that you can always breathe before, during and after a theatrical performance.”

He was only 13 when his Uncle Giuseppe – who would play a fundamental role in addressing his young nephew towards an artistic career, in the years to come – introduced him to Neapolitan conductor Gennaro Papi. At that time he was in New York to conduct Puccini’s Bohème and was also one of the closest assistants to another Italian celebrity, Arturo Toscanini.

The Metropolitan Opera Theater, until the end of the 50s, was located at the corner between 39th Street and 7th Avenue. It was in that theater that the adolescent Coppola had the good fortune of seeing people the caliber of Martinelli, Pinza, Bori (operatic Italian glories at the beginning of the XX century). Too young to have seen Caruso, he likes to say, though, that akin to what Pavarotti did many decades later, Caruso “was the fulcrum of national pride and glory. It was important for us to show that we could offer not only hands for factories, but that we were also enormous exporters of Art and Culture, both elements wonderfully summarized in the melodramatic genre.”

The beginning? Not easy, like in every respectable story, but in Coppola’s case, there had also been many fortunate meetings. “One day, maestro Papi decided to audition me. I was so nervous. I started playing and singing some opera scores. He liked me very much and, since he was living alone in NY, adopted me like a son. It was a beautiful teacher-student relationship. He would invite me to the performances and the day after he would phone and ask what my opinion was about the previous night’s show. We would have very long conversations and Papi always showed deep interest in my opinion. He would then go over the most difficult passages of the score and say: «See, Anton, if you happen to conduct this opera, be veeeeeeery careful of this passage»!!!”

Papi also convinced his talented pupil to start practicing another instrument besides piano, “it’s good in order to have a better understanding of the orchestra musicians’ jobs. In this way you know what you really can ask of them! – he used to repeat – and so I learned how to play oboe under the guidance of Bruno Labate”, the first oboist in the New Philarmonic during the Golden Era of Toscanini’s baton.

“On a Saturday morning, like every Saturday, there was the Matinée at the MET. I don’t honestly remember what opera was to be performed, but I vividly remember that Maestro Papi didn’t show up. A few hours later we learned that he had died of a heart attack. When a mentor like him suddenly disappears, it leaves a wound in your soul that is difficult to heal and creates a huge void in your life; if I’ve become someone, it’s mostly because of people like Papi, a great man and musician!”

Family also played an important role in Coppola’s career. Agostino, his father, was a lathe turner. “A father of 7 children, when he came back from work, he wanted to see all the kids gathered around the table. When my mother yelled: «Guys, come eat»! - my father, would point his finger towards me and would often say: «Leave him alone, he’s studying»!

This concession often made me feel special and gave me a bigger sense of responsibility towards my parents, although I should say that I never too much affected them financially, having been lucky enough to receive free lessons for all of my training period. Maybe because in the years of my apprenticeship, from 1929 to 1940, things were different: there was less money and more values. Many teachers believed in their students and transmitted to them all of their science in a free and disinterested way, in the same way their teachers had formerly done with them.”

It’s also true that Coppola’s apprenticeship years coincide with what so far is considered to be the worst period of economic and financial crisis in the United States. In order to find a remedy for the deep economic depression the country was experiencing, the Roosevelt Administration launched the so-called “New Deal”. It was an innovative economic program in which one of the projects, the WPA (Work Progress Administration) guaranteed that all the workers would receive a salary of 23 dollars per week, no matter what job they were performing or what professional category they belonged to. In this way it was possible to quickly reduce the percentage of unemployed people in the country.

“During the ‘great depression’ period in NY, there were 5 symphonic Orchestras and a permanent Opera Company, whose resident conductor was Fulgenzio Guerrieri, from Torino, “ what we would call a living encyclopedia; he knew almost everything, with only one big flaw: he was too attached to the bottle. Even if it’s not pleasant, put it down in this way, this has been my fortune. In fact, once I became his assistant, I was put in charge of rehearsing with the Orchestra members and when the opera was ready, Gurrieri would perform it in the 5 boroughs of NY: 5 performances, one for each borough and then he we would start over with new titles.”

In 1936, on a Sunday morning, there was the last performance of Samson et Dalila by Saint-Saëns and Gurrieri wasn’t feeling well. I had already gone through the whole rehearsal period with the Orchestra, so I knew the opera very well. Therefore, when they asked me to jump on the podium, grab the baton and give instructions to the musicians in the orchestra pit, I didn’t hesitate a second!”

Also in 1936, Coppola ran for the position of primo oboe in the Radio City Music Hall Orchestra, a 50 element orchestra, “they were all very talented musicians; it was a job where my paycheck finally got a little bit bigger!

When World War II deflagrated, I was recruited as a simple soldier. One day, walking around, I noticed flyers posted all over regarding a band conductor position. It was a 3-month training course. I applied and was accepted. After the trimester training, they sent me to Texas to conduct an aviation camp band. We twice got the leave order, but thank God both times the order was canceled”.

Not an easy situation for Coppola, son of Italian parents, born in the USA and recruited to fight a war that, at least in the first phase, saw Italy among the hostile countries. “My father would often repeat: we are in the United States and we’ve got to behave as respectful guests of this nation. He didn’t care at all about Mussolini. Those who were fascists in the United States didn’t know anything about fascism: what they would see here was another thing; it was only the folkloristic aspect of that political tragedy. Others were just chasing some sort of utopia, and ignoring the potential consequences.

Yet fascism and its proselytism in the United States caused a certain type of diffidence towards Italians and reinforced preexisting prejudice towards Italian/Americans. It’s worth saying, though, that it was never as severe as it was for the Germans or the Japanese, who, after Pearl Harbor, were literally deported to concentration camps.”

By the time the war was over, Coppola had been contacted by San Carlo Opera Company, which had nothing to do with the prestigious Neapolitan Theater (Teatro San Carlo). The manager of this company, Fortunato Gallo, was in charge of organizing a tour throughout United States and Canada. The company would perform a different title every night. The repertoire was quite traditional, except for Wagner’s Lohengrin, the only German opera present in their season. “They were looking for a conductor and after an audition, I got the job. This put me under a very intense operatic schedule, since I had to conduct, night after night, the most famous operas of the repertoire. The end of the tournèe was held at New York Center Theater. That night we were performing Bizet’s Carmen. The general manager of New York’s Radio City Music Hall came to see me on the podium and the day after invited me to conduct there. It was there that I met a very pretty dancer named Almerinda Drago, whose parents were from L’Aquila”. Two years later Almerinda became his wife and the mother of their two children, Bruno and Lucia, “who speak Italian like Roman senators! From the very first day that we brought them from the hospital, Italian was the only language we spoke with them.” Coppola and his wife have just celebrated 57 years of marriage.

A significant change in Coppola’s career came in 1952, when he was called to conduct a particularly difficult show, offered to him because: “they needed a conductor with an operatic background and a familiarity with a more complex repertoire.

This started Coppola’s adventure with Broadway, which kept him busy for 10 years, during which he conducted The Boyfriend (1954 with Julia Anders), New Faces (1952) and Silk Stocking (1954). In 1958 he conducted “The Most Happy Fellow”, the story of an Italian emigrant who didn’t speak English very well and finally My Fair Lady, one of the most popular shows of all times in which he conducted the second company.

A few years later, the Manhattan School of Music contacted Coppola about a teaching position. “They were doing Puccini’s Gianni Schicchi and Ravel’s Heure espanol. They hired me, and so I became responsible for young people in symphonic and lyric orchestras. Working with young talented people is an unforgettable experience.” His work at the Manhattan School of Music continued for 15 years. In the intervening time, Coppola began intensifying his schedule as guest conductor.

From 1977 on, Coppola decided to only work as guest conductor, mainly due to the many requests he received from all over the world. This choice enabled him to accept prestigious engagements, like the one at New York City Opera, where he conducted the world premiere of Jack Beeson’s Lizzie Borden, of which he also conducted the first recording. With regard to world premieres, he also conducted Carlisle Floyd’s Of Mice and Men, first performed at the Seattle Opera in 1970.

Under his baton passed important names the likes of Luciano Pavarotti, of whom Coppola conducted the American debut in San Francisco’s Bohème. Next to Big Luciano, who is known to larger audiences, appear names like Siepi, Giaiotti, Tucker, Merrill, Peerce, Consiglio, Scotto, Di Stefano, and Stella; a list of operatic stars that would make Coppola envied even by the most famous conductors of the moment.

“All the singers I have worked with respected me and have never been temperamental. They have always considered me a representative of the Old Italian School and were mostly eager to learn from my experience and knowledge. If the young conductors nowadays listened to the few conductors left of my age, perhaps Opera would have a better future and it wouldn’t be forced to become something else or to resemble more and more to other genres”.

Despite age – whether he is older than 80 or younger than 80 doesn’t really matter – Anton Coppola still shows incredible energy, to the point that he recently recorded a Puccini operatic anthology for EMI with the soprano Angela Georghiou and the Orchestra Sinfonica di Milano Giuseppe Verdi.

On the compositional side, Coppola gave a noble contribution with his opera Sacco and Vanzetti, based on the story of two Italian anarchists whose execution is still a controversial topic amongst historians.

“About 10 years ago my nephew Francis phoned me with an idea of doing a documentary about these two anarchists who were put to death on the electric chair in 1927. «If you want – he said – you could try to write 4 or 5 pieces». After he had heard the pieces, he called me: «Uncle, but this is an opera»! I interpreted his opinion as a sign of encouragement to continue and got extremely passionate about the subject, reading all I possibly could read and learning all I could learn about the different theories and reasons regarding why these two Italians were condemned. First I wrote the libretto and then the music. I wanted the libretto to be bilingual, in order to respect one of the most peculiar features of the Italian/American Community in the 20s.

As a matter of fact, they spoke Italian when they were with their fellow countrymen and English in their day to day lives and therefore forced to make themselves be understood.”

The world premiere was held in Tampa (Florida) in 2001, with a 24-singer cast, chorus and traditional orchestra enriched by 5 band instruments and 160 costumes. The success attributed to the Opera by the critics and the audience makes it difficult to understand why, besides Tokyo and Trieste, no other theaters have showed interest in the title.

“I remember that in my family, as in many others, we discussed a lot whether they were innocent or guilty. I want to say, though, that the goal of the Opera is not to prove them innocent, also because in my opinion Vanzetti was undoubtedly innocent. Perhaps Sacco was too. The purpose is rather to raise the question: was the trial fair? Was justice fair in that situation?

Apparently not, since the judge who was expected to write the verdict, walked out of his golf country club, saying: «you’ll see what I’ll do with those bastards»! We must admit one thing: whether innocent or guilty, there was a huge prejudice against them: they were Italians and anarchists and this very much affected the final decision”.

In fact even representatives the US Justice department recognized it as a mistake 50 years later.

“Sacco and Vanzetti’s story is a very significant one, emblematic in shedding some light on the actual situation that many Italian emigrants had to face, in the USA at the beginning of the XX century. Often we talk about the many achievements of Italian/Americans of second or third generation in various fields, but we forget the sacrifices and often the discrimination that our parents and grandparents endured.

My nephew Francis Ford Coppola is really devoted to his family and his Italian heritage. Just a year ago he bought the biggest Villa in the center of Bernalda and named it Villa Coppola. Bernalda is the place from where my father emigrated when he came to the United States. I get goose bumps if I think about it.

My father walked out of that village with nothing and now his name returns on the walls of the most sumptuous villa. I know that he would be happy, because he, like me, always loved his country and the values that we have been able to export all through the rest of the world. As a musician, I’ve always been proud to be an ambassador of an unbeatable historical, artistic and cultural patrimony”.

Anton Coppola fulfilled his duty wonderfully. Thank you, Maestro!

i-Italy

Facebook

Google+

This work may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without prior written permission.

Questo lavoro non può essere riprodotto, in tutto o in parte, senza permesso scritto.