You were born in the little southern Italian town of Lagonegro, in the Basilicata region. What do you remember of the last day in your hometown before emigrating? And what’s the first thing you remember about America?

I remember particularly that mom and dad brought me to Sapri to take the train, and it was probably the only time they actually drove me anywhere. It was so beautiful and spontaneous, it was a beautiful day. It was March 1989. I don‘t feel sorry because I left, but I feel more for Basilicata now. I think I do more for the region now than if I were still there. It’s my goal to promote Basilicata all over the world. This is very important to me. I started a nonprofit organization back home called Basilicata: A Way of Living to find the old traditions, the things about Basilicata the world should know, and protect them for a new generation.

You are very well known chef. Did you dream of being one as a child?

I don’t know about a dream, but I do know I always wanted to help my mom and on one occasion I was cutting the peppers trying to imitate her and how she made fettuccine. As I was cutting the peppers I said, “Mom I was making my own fettuccini for you!” Growing up on a farm, the only things we bought were sugar, coffee, and salt. We grew or made everything else.

You studied at the culinary institute in Maratea and then worked in Italy and else- where in Europe, but you said you came to America by chance. How did you get to Washington?

I think Washington picked me. People would call to ask me to work with them. Because once you reach a certain level, the work will call you. During that time, the late 1980s, someone in Washington called looking for a chef, asking me to find someone. No chef wanted to come and work in the US then, and neither did I. The hot place was Italy, then Spain, France, Switzerland, London. Today, everyone wants to come to the United States. My contact never could find a chef, and two weeks later asked me to come over. Six months later I was here. Washington was really shocking because I did not know the language, and nobody knew that I was coming.

When did you decide to open your own restaurant?

When I saw what Washington restaurants were offering, I realized there was so much more I could do. I was going to school to learn English, and I told myself that if there were going to be survivors in those tough times, I would be one. I was going to make it! I realized, you know, there was such a need for good food, and that I should see if I could do better. I promised myself that if could not open my own business in five years, I would go back to Italy. I was able to open Al Tiramisu in three and a half years.

Why did you call it Al Tiramisu? Tiramisu wasn’t a famous dessert then.

I wanted a positive name for my restaurant. I debated between Girasole, which means sunflower, and Tiramisu, since they are both positive and fun. Tiramisu means cheer me up. I think the atmosphere of Al Tiramisu is a complete package. It’s small, only eighteen tables, a classic, elegant trattoria where locals go because it’s a good atmosphere with serious food. That’s what I created in DC. When you walk in, you feel like you are in Italy-- the music, the color, the decor, and most important, the food. Everybody works to make sure the food is perfect, fresh, tasty, and kind of like a hug. That’s our secret.

How did you end up in the American Chef Corps of the White House?

The group was created by Hillary Clinton when she was Secretary of State to use food for diplomacy. As we say, at the table you ever get old, and you never fight. I believe the Corps has about eighty five chefs all over the US right now. I feel honored and proud, because I think I am the only native Italian member.

After all these years in Washington, do you think you’ve contributed to the education of Americans about la cucina italiana?

Absolutely! I remember the days when people would ask what rucola was, or fennel. In the beginning I would spend more time in the dining room presenting our special products, like sardines. I remember when branzino and orata would come from Italy only on Tuesday. Now, it‘s seven days a week. In the last ten years, we have been hit by a tsunami of food, a food revolution.

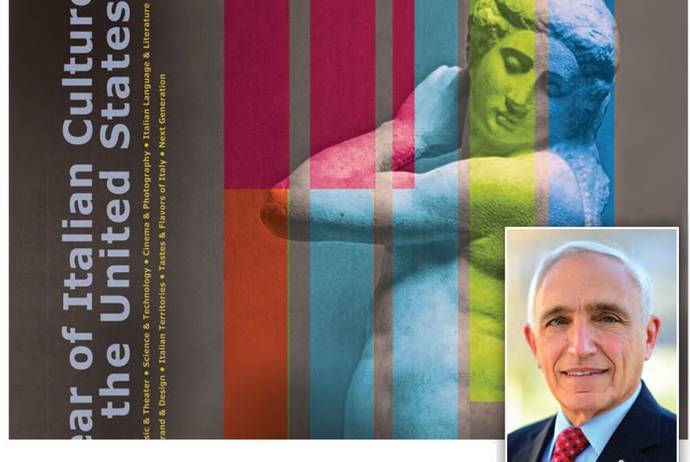

You are well known and loved in the Italian American community in Washington. How did you meet the community at NIAF?

Well, wherever there is Italy, wherever there is my Basilicata, I am at the front of the line. This is one of the great associations of Italian Americans and I am proud to be a member. I support a lot of NIAF‘s events, like the gala. I have done great events in the past, including one to promote the culture, cuisine, and wine of Calabria. I think that John Viola has started a new direction that I am a big fan of. It will inspire more young people with a different approach, and get them closer to the National Italian American Foundation. I think he is doing a great job.

When you retire will you go back to Italy and open a restaurant?

Oh well, I’ll go back for sure, but I don’t know about opening a restaurant!

Let us end our conversation with a very delicate question for a chef—What is your favorite Italian dish?

That’s a good question because I have a problem: I like all kinds of food, and it shows! But how can I not like pasta? In particular I like pasta e fagioli, homemade, because it’s one of my oldest food memories. Next to our fireplace was a terracotta pot full of beans that would cook all day, and when I came home hungry from school, I would take bread and dip it inside.

Al Tiramisù: The Book

A Cross-Cultural Culinary Journey from Basilicata to Washington, D.C.

Chef Luigi published the Al tiramisu restaurant Cookbook in December 2013. Co-written with award-winning author Amy riolo, this unique collection of more than 100 mouthwatering recipes reveals the history of Al tiramisu, Washington, DC’s “most authentic” Italian restaurant, as well as the life story of Chef/owner Luigi Diotaiuti. the book welcomes readers to Al tiramisu - sharing memories and favorite dishes of both celebrity diners and cherished clients. Chef Luigi then leads a culinary tour back to his homeland of basilicata, Italy (where he was recently awarded the Ambassador of basilicata’s Cuisine in the world by the federation of Italian Cooks) and shares secrets from some of the finest dining establishments around the globe where he began his career. the final chapter outlines the chef’s life in America and includes recipes that he served at the James Beard Foundation and in cross-cultural culinary venues on both sides of the Atlantic. each beloved recipe represents Al tiramisu’s “elevated” Italian cooking style and features an Italian cooking tip and a wine pairing.

2014 P St NW, Washington, DC 20036

Click here to watch the interview Ottorino Cappelli did with Chef Luigi Diotiaiuti.

This interview is part of the TV series ‘Italian Leadership in America,’ a co-production of i-Italy and the National Italian American Foundation.