Protecting Pompeii and the Italian Heritage in 2012

This is not the first time. In 2004, the charity tax fund was diverted to help fund the war in Iraq, under a slogan, perhaps, of “make war not restorations.” This year’s call is more comprehensible, but nevertheless a choice that should not have been imposed in Italy, a country which quite properly takes pride in, and makes money from, its myriad splendid cultural heritage sites and museums, and has an obligation to protect its heritage, down to and including its medieval archives.

On the other hand, the Minister of Culture, political scientist Lorenzo Ornaghi, who was, untilentering the Monti government last month, rector of Milan’s Catholic University of the Sacred Heart, may have reasoned that enough money is being poured into Pompeii to compensate for a cut-back even if other cultural areas will be penalized. It is true that Pompeii has been crying out for help. In November of 2010 the Domus of the Gladiators collapsed, followed by a 24-foot section of ancient city wall. A few days before Christmas 2011 a pilaster holding up the pergola at the lovely House of Loreio Tiburtino fell down. “This confirms the fragility of Pompeii,” said the General Secretary of the Ministry, the architect Antonia Pasqua Recchia.

The sense of urgency is palpable, and among others regional governor Stefano Caldoro recently met with an American movie producer interested in developing multimedial theaters. For Pompeii Caldoro also favors more hotels, restaurants, tour routes and cruise ships. Fortunately, other help is on the way. The European Commission has now confirmed that it will provide $61 million of immediate EU emergency funding for thirty-nine projects at Pompeii plus another $49 million by the autumn of 2012. UNESCO funds of $136 million are also en route to Pompeii, under the terms of a three-year plan aimed toward an upgrade of restoration efforts.

For a sponsor, Pompeii with its 5 million annual visitors would presumably be a high-class cultural boom box, and so Epadesa, a consortium of 2,500 primarily French businessmen, in coordination with local Neapolitan businesses and industry, is offering from $7 and $14 million annually to sponsor restorations “adoptions” of endangered Pompeian buildings. Similarly, restoration of the Roman Colosseum was awarded to a single sponsor, shoe manufacturer Diego Della Valle, and the pyramid of Caius Sestius will be restored by a Japanese businessman. Just how this sponsor-partnership will work out at Pompeii remains to be seen. In the meantime there are local protests that details are fuzzy and that not all the areas at risk in the Vesuvian sites are receiving the same degree of attention, with Stabiae at the bottom of the priority list.

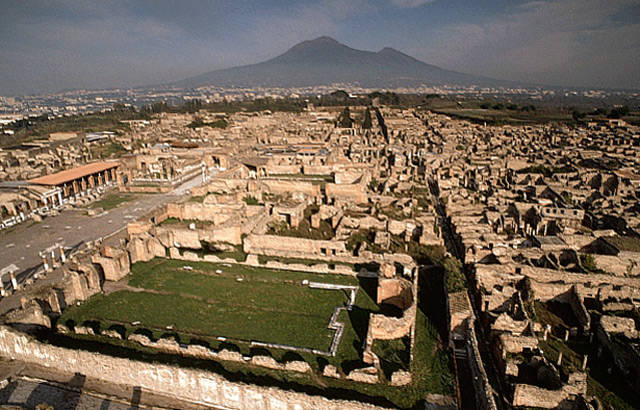

None of these problems is new. Back in 1996 the World Monuments Fund reported that the “major risks result… from excessive public access, atmospheric exposure, erosion, etc.” The following year Andrew L. Slayman, associate editor of the U.S. magazine Archaeology, wrote that the problems begin with the vast size of the exposed site, 110 excavated acres (of 163 within the walls). In addition, Slayman wrote, “Routine wear and tear caused by tourists is the source of much damage. Manpower and funding are also sources of frustration.” Slayman was particularly critical of Baldassare Conticello, Superintendent of Pompeii from 1984 to 1994, because, under pressure from papyrologists from universities all over the world, Conticello had permitted the open-air excavation of the Villa of the Papyri at Herculaneum. The villa, which had yielded the only known library from antiquity, had lain sealed deep underground for over two centuries. Although the Getty Foundation picked up the bill, the criticism continued, and a moratorium on new excavations was imposed until Pompeii could be maintained properly.

Yet Conticello, with experience working in Libya and elsewhere, knew the problems as well or better than anyone. Some twenty years ago he took me for a tour of Pompeii. Pointing to a city wall, he said, “Look how fragile that is—it’s been exposed to the elements ever since it was brought back to the light of day 250 years ago. Weeds grow on it. Unless they’re removed, they can eventually bring down the whole wall, but we need a weed-killing substance that won’t destroy what is underneath.”

Since Conticello was replaced in 1994 there have been no new digs, and yet the lack of maintenance today has made headlines all over the world. Three superintendents and a special emergency commissioner later, the problems are the same or worse today, suggesting the existence of some basic underlying problem which has not been addressed by anyone. For one thing, today’s administration of Pompeii is further hampered by the present Superintendent’s being required to oversee a territory that includes Naples as well as Pompeii. In fact, UNESCO will send advisors, but my feeling is that a world-wide conference of scholars should also be convened, and that the Italian government should begin to listen to not three or four experts, as is now the case, but to many, and only then take action.

Prof. Conticello died Dec. 29. Today he is remembered as a pioneer in applying modern archaeological methods, the link between the old way of managing a site and today’s more modern, if still deeply compromised manner of dealing with Pompeii. At his funeral in Rome the archaeologist Antonio Varone said that Conticello will be remembered for his particularly broad interdisciplinary background, which is why he listened to the papyrologists. Conticello initiated the first program to educate the custodians about the site they guarded. And for the first time on his watch computer models of Pompeii were put to use, by such outstanding scholars as the American Prof. John Dobbins. [See the video]

i-Italy

Facebook

Google+

This work may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without prior written permission.

Questo lavoro non può essere riprodotto, in tutto o in parte, senza permesso scritto.