For Augustus Bimillennary, House of Livia is restored

ROME – A bright new star shines in the spangled firmament of Roman wonders as of this week. Okay, maybe not so new: among the commemorations of the second millennium of the death of Caesar Augustus on August 19, 2014, is restoration of the fabulous villa owned by the family of his beloved wife, Livia. Elegantly restored thanks to state-of-the-art technology, it now has a small, fascinating mini-museum, or antiquarium.

The sprawling villa at Prima Porta, built 2,000 years ago, was a working farm, but also for the emperor and for his wife Livia a place for meditation, study and relaxation. Situated on a hilltop just north of Rome, it overlooks the ancient Via Flaminia and a bend in the broad Tiber River, and is not to be confused with the House of Livia on the Palatine Hill in central Rome. Here Livia had her own small garden of medicinal plants used for herbal teas. Nearby were fruit trees plus a huge formal garden built upon an artificial terrace high above the river. Divided into squares, the terrace has laurel trees growing from great terra cotta pots; their leaves were utilized for the laurel crowns worn by the emperor. Archaeologically correct, the laurels have been replanted for the commemoration.

Livia Drusilla was the daughter of a Roman noble from the Claudian family. Like Augustus, she had been married before – in her case, to her cousin Tiberius Claudius Nero. In a rapturous love affair she was speedily divorced to marry the enamoured Augustus. They had no children, but she became his influential counsellor and virtual empress. She had a bad press and was depicted as cold and calculating, but some of today’s scholars question this on the basis of her life style, modest for the wife of an emperor.

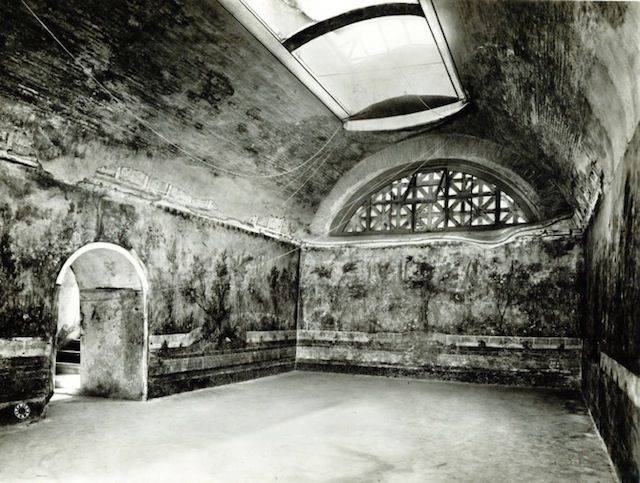

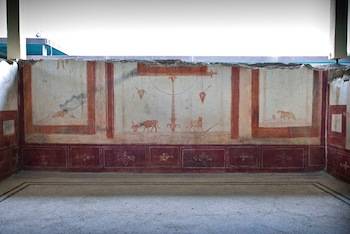

For centuries after imperial Rome the villa had been farmed, and traces of the passage of a plough are visible. In 1863, after centuries of abandon, excavators discovered important sculptures on the site. Among these was a statue of Augustus, which went to the Vatican Museums. At the same time the most famous of the villa’s wall paintings was found, the rectangular garden fresco which had covered the walls of a subterranean winter garden (ipogeo) abutting the guest quarters of the villa. Various attempts to remove it were made, and succeeded only in 1951, when the winter garden had become so damp that the frescos risked destruction. At that point they were successfully detached and removed to Rome, where they can still be seen, in excellent condition, in the national archaeological museum in Palazzo Massimo, near the Terminal railway station.

The imaginative restoration of the villa – huge swimming pool, winter garden, guest rooms, the latrine, the nearby bedrooms of the emperor and Livia herself, and much more – is of the highest level and, above all, subtle. The restorers had only six months to remove a thick, uniformly cream- colored layer of calcium carbonate which entirely covered the painted surfaces of those walls which have survived, usually no more than waist- high. To clear this away they used a three-pronged combination of state-of- the-art technologies: chemical, machine and laser.

The results are amazing: delicate candelabras, sea horses, a panther with wings. In addition to the ravages of time, during World War II bombs fell directly into the villa, and traces of the fires they started are visible in some of the frescos in the guest quarters.

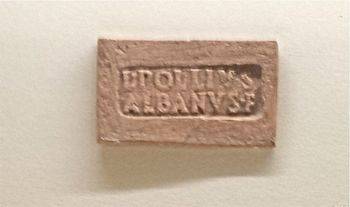

Among the treasures of the small new museum, the “Antiquarium,” are clay lamps, tiny glass bottles, fairly modest finger rings, iron keys, and plaques, like the 5-inch-long terra cotta panel which the plumber responsible for the latrine drainpipe had inserted into the drain, either out of pride or because – if it did not work properly – he would have to answer for a clogged toilet drain. If not on the order of the Emperor Augustus, his name, two millennia later, survives: L. (for Lucius) Pollius Albanus.

i-Italy

Facebook

Google+

This work may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without prior written permission.

Questo lavoro non può essere riprodotto, in tutto o in parte, senza permesso scritto.